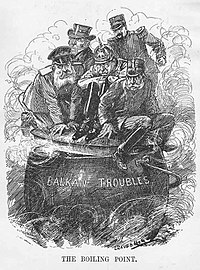

World War I represented a collapse of tenuous diplomatic supports across Europe. There had been a long buildup of animosity between nations.

Competition for various colonial territories and their natural, cultural, and human resources was driven by nationalism.

Pride and prestige of a sovereign nation also came about by building up military strength. A large standing army is a very persuasive instrument of diplomacy.

Industrial-scale machines such as the then-contemporary Dreadnought and Super-Dreadnought classes of battleships were high-profile exhibitions of nations' dominance.

It was primarily England and Germany in the top tier of this arms race. Smaller or less industrialized nations felt they needed a strong ally to defend them,

hence the network of interrelated military agreements that pulled everyone into the fracas.

World War I represented a collapse of tenuous diplomatic supports across Europe. There had been a long buildup of animosity between nations.

Competition for various colonial territories and their natural, cultural, and human resources was driven by nationalism.

Pride and prestige of a sovereign nation also came about by building up military strength. A large standing army is a very persuasive instrument of diplomacy.

Industrial-scale machines such as the then-contemporary Dreadnought and Super-Dreadnought classes of battleships were high-profile exhibitions of nations' dominance.

It was primarily England and Germany in the top tier of this arms race. Smaller or less industrialized nations felt they needed a strong ally to defend them,

hence the network of interrelated military agreements that pulled everyone into the fracas.

Each primary nation involved in World War I had the notion that it would be decided quickly. The Germans had their Schlieffen Plan drawn up tightly,

expecting to sweep through France so quickly as to be able to bring the very same forces to bear against the inevitable Russian attack on the opposite

side of the country. They had expected England to stay out of the war until decisiveness over France had been achieved.

Germany's ambitions exceeded its abilities, and months dragged into years of expensive, unpleasant deadlock in the trenches.

The public in the Fatherland was kept ignorant of the true state of the war, even while food and other neccessities were becoming scarce.

Modern weapons were used for the first time in The Great War. Machine guns could mow down entire lines of troops, so the frontline dug into trenches.

Airplanes were used to spot these trenches, direct artillery, and eventually drop bombs. Tanks could carry a big gun through barbed wire with impunity from small arms.

Submarines could bring down ships before even being spotted. Chemical weapons made a horrific debut.

Each primary nation involved in World War I had the notion that it would be decided quickly. The Germans had their Schlieffen Plan drawn up tightly,

expecting to sweep through France so quickly as to be able to bring the very same forces to bear against the inevitable Russian attack on the opposite

side of the country. They had expected England to stay out of the war until decisiveness over France had been achieved.

Germany's ambitions exceeded its abilities, and months dragged into years of expensive, unpleasant deadlock in the trenches.

The public in the Fatherland was kept ignorant of the true state of the war, even while food and other neccessities were becoming scarce.

Modern weapons were used for the first time in The Great War. Machine guns could mow down entire lines of troops, so the frontline dug into trenches.

Airplanes were used to spot these trenches, direct artillery, and eventually drop bombs. Tanks could carry a big gun through barbed wire with impunity from small arms.

Submarines could bring down ships before even being spotted. Chemical weapons made a horrific debut.

Nations poured manpower into the teeth of these killing machines until it was finally basically attrition that ended Germany's ability to fight.

The home front was a new concept in this era. Before, military efforts were confined to the military. It was realized that an enthusiastic, nationalistic civilian

population would be instrumental in conducting an all-out worldwide war. The currency of the war effort was materiel, which had to flow constantly to the frontlines.

Civilians were now coerced to sacrifice their luxuries in the name of their countries' righteous efforts on the battlefield. Food was to be produced to feed the army.

Clothing had to be militarily functional. Metals would need to be directed to applications of importance to the war effort rather than to the whims of convenience.

Ammunition had to flow steadily. With much of the male population of working age fighting in the field, women were put to task in fields previously believed to be

outside their realm of ability or outside of what had been considered appropriate for them to do.

The home front was a new concept in this era. Before, military efforts were confined to the military. It was realized that an enthusiastic, nationalistic civilian

population would be instrumental in conducting an all-out worldwide war. The currency of the war effort was materiel, which had to flow constantly to the frontlines.

Civilians were now coerced to sacrifice their luxuries in the name of their countries' righteous efforts on the battlefield. Food was to be produced to feed the army.

Clothing had to be militarily functional. Metals would need to be directed to applications of importance to the war effort rather than to the whims of convenience.

Ammunition had to flow steadily. With much of the male population of working age fighting in the field, women were put to task in fields previously believed to be

outside their realm of ability or outside of what had been considered appropriate for them to do.

The March Revolution was a culmination of pent-up resentment for the arrogance of the Tsarist regime. The war against Germany was costly and unpopular, causing

food shortages for the vast working class. When the provisional government took over, it was too little too late to satiate the people's desire for profound reform.

The war continued even while the chain of command was rumpled by the soviets' Order Number 1. Redistribution of wealth was expected, but the provisional government,

whose leaders primarily favored the elites, dragged their heels. Bolshevism, propounded by Vlad Lenin, spoke loudly to what the masses wanted to hear: the farmers

should own the land they work, the factory workers should own the machines they operate, and Russia should exit the war immediately. Lenin had not only the unpopularity

of the Kerensky administration in his favor, he had steadfast idealism and the social-engineering maneuvers of Leon Trotsky.

The March Revolution was a culmination of pent-up resentment for the arrogance of the Tsarist regime. The war against Germany was costly and unpopular, causing

food shortages for the vast working class. When the provisional government took over, it was too little too late to satiate the people's desire for profound reform.

The war continued even while the chain of command was rumpled by the soviets' Order Number 1. Redistribution of wealth was expected, but the provisional government,

whose leaders primarily favored the elites, dragged their heels. Bolshevism, propounded by Vlad Lenin, spoke loudly to what the masses wanted to hear: the farmers

should own the land they work, the factory workers should own the machines they operate, and Russia should exit the war immediately. Lenin had not only the unpopularity

of the Kerensky administration in his favor, he had steadfast idealism and the social-engineering maneuvers of Leon Trotsky.